Snakes are terrifying. Those cunning eyes, enigmatic movements, and lethal venom always evoke a sense of primitive fear in us humans, yet the snake happened to find itself in the most well-known symbol of healing and medicine – the staff of Asclepius. The snake symbolizes both good and evil, light and darkness, yin and yang, and that makes it such an interesting creature in art and history.

In this article, we will explore in-depth the snake symbolism in cultures and mythologies across the globe.

1. Danger

The roots of our fear of snakes lie in our evolutionary past, embedded in the mechanisms of our brains that swiftly identify potential threats such as snakes and spiders. This primal fear reflects our ancestral instincts as primates, developed over millennia to recognize and avoid dangers that once threatened our survival.

Consider this timeline: mammals have thrived for about 83 million years, while snakes have roamed the Earth for approximately 100 million years (latest fossils date back to around 160 million years). For humanity, snakes have represented a genuine threat since the earliest hominids walk the planet some eight million years ago.

The prevailing consensus is that our species evolved in Africa, a continent teeming with snakes. In such an environment, life must have been scary indeed, shaping our ancestors’ instincts and deepening our inherent fear of the snake. In our collective unconscious, the snake symbolizes fear, and most probably, death.

Read More: 23 Symbols of Death and Their Meaning

2. Venom

When talking about “venomous creatures”, some of the first creatures we thought of are usually the snakes. The snake venom is a potent saliva which contains toxins that help paralyze and digest prey, while also serving as a defense mechanism against threats. It’s delivered through specialized fangs during a bite, with some species also capable of spitting venom.

Some snake venoms are highly potent and can cause rapid paralysis, organ failure, and death if left untreated. Others can cause severe tissue damage, pain, and other symptoms but are less likely to be fatal.

3. Medicine & Healing

Interestingly, it is the same venom that kill humans at a tiny dose turns out to have amazing healing properties. Ancient civilizations recognized the dual nature of the snake venom — they could both heal and harm. The snake symbol was then linked with Asclepius, the ancient Greek God of medicine, representing benevolent healing properties. According to belief, its mere touch could cure illnesses or wounds.

There is a story behind why the snake was used in the medicine symbol. While on a journey to visit a friend, Asclepius encountered a snake. He extended his staff, and the snake coiled around it. Seeing this, Asclepius struck the ground with his staff to kill the snake. However, another snake slithered up, carrying a herb in its mouth to heal the wounded snake. From this incident, Asclepius began to search for various herbs on the mountains to heal and save human lives.

As a tribute to Asclepius, a specific type of non-venomous rat snake, known as the Aesculapian snake, played a central role in healing ceremonies. These snakes freely roamed the dormitories where the sick and injured rested. They were a customary presence introduced during the establishment of each new temple dedicated to Asclepius across the classical world.

Particularly noteworthy is the ancient Greek term for medicine, pharmakon, from which we derive words like pharmacy and pharmaceutical, meaning both “drug” and “poison”.

The snake symbolism for healing also stems from its regenerative ability. Snakes can shed their old skin and emerge with a fresh one. In many cultures, this aspect of snakes is seen as a metaphor for the healing process, where people successfully overcome illness or injury and emerge revitalized.

4. Duality

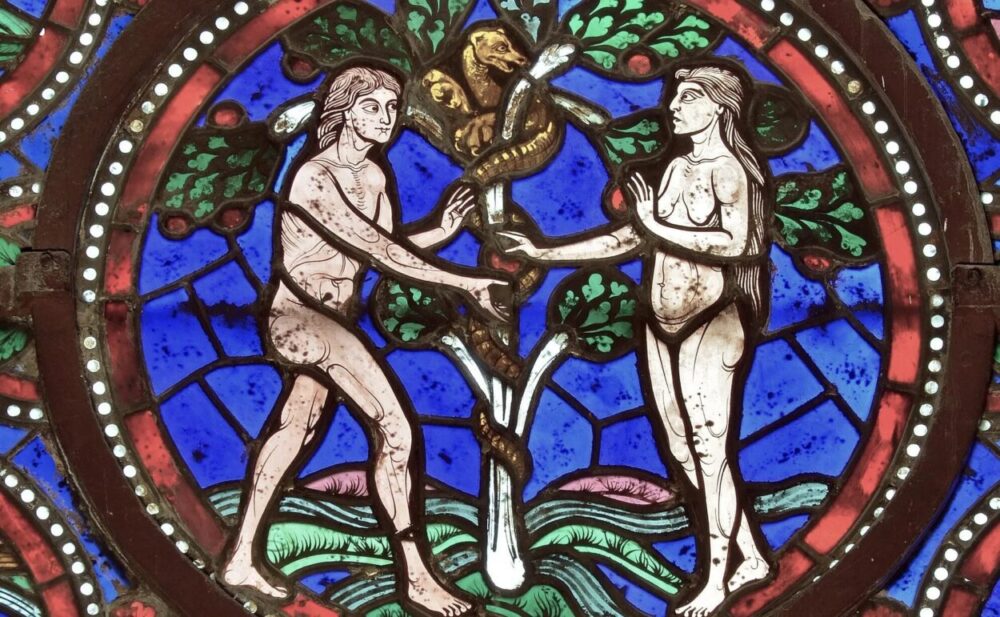

We can obviously see the dual nature of the snake. It can both heal and kill, both good and evil, both light and darkness. This duality occurs in the story of Adam and Eve in the Bible. According to the Book of Genesis, the serpent is portrayed as the most cunning of all creatures created by God. Like Adam and Eve, it possesses the ability to speak and reason. Seduced by the serpent’s persuasion, Eve partook of the forbidden fruit, followed by Adam, leading to the opening of their eyes to newfound knowledge, knowing “good and evil”.

The story of Adam and Eve is often interpreted as symbolizing the transition from a state of innocence and unity with the divine (the all-inclusive, non-discriminating mind of God) to a state of consciousness characterized by the ability to discern between good and evil (the discriminating mind).

Read More: Symbols of Innocence and What They Really Mean

The consumption of the forbidden fruit represents the moment when we must be separated from the undifferentiated source to assume a differentiated existence (hence the “expulsion from the Garden of Eden). The snake stands in the middle of this duality, symbolizing the ultimate transformation of non-existence to existence.

The snake here is said to be a female snake. The medieval Christian art often depicts the Snake in the Garden of Eden as a woman, thus emphasizing both its tempting nature and its relationship with Eve. Many authorities in the early period, including Clement of Alexandria and Eusebius of Caesarea, explain that the word “Heva” in Hebrew not only means the name of Eve but in its vocal form, it also means a female snake.

5. Wisdom

In various mythologies, snakes have been linked to wisdom, possibly inspired by their deliberate, contemplative movements before striking, a behavior emulated by medicine men in West Africa before prophetic practices. Typically, snake wisdom was seen as ancient and advantageous to humans, though occasionally it could be turned against them.

In East Asia, snake-dragons guarded over bountiful harvests, rain, fertility, and the seasonal cycle, while in ancient Greece and India, snakes were deemed auspicious, and snake amulets were employed as safeguards against malevolence.

Even Jesus advised his followers to “Be wise as serpents”. Some gnostic groups, known as the Naasenes or Ophites, revered the serpent as a representation of knowledge and salvation.

In Aztecs and other Mesoamerican cultures, Quetzalcoatl is one of the most important and revered deities. Quetzalcoatl was born to the primordial goddess Coatlicue, who became pregnant after a ball of feathers fell from the sky and landed in her womb. This miraculous conception led to the birth of Quetzalcoatl and his twin brother Xolotl, who was associated with the evening star.

Quetzalcoatl is often portrayed as a benevolent deity associated with creation, knowledge, arts, culture, and civilization. He taught humanity various skills and arts, including agriculture, metallurgy, and calendar-making. He was also considered the patron deity of priests and rulers.

6. Guardianship

Snakes also symbolize guardianship in ancient cultures. In Hinduism, the serpent god Shesha is depicted as a guardian of the universe. Similarly, in Egyptian mythology, the uraeus, a symbol of a rearing cobra, was worn by pharaohs as a symbol of protection.

This association may stem from the observation that certain snakes, like rattlesnakes or cobras, often stand their ground when threatened. They employ threatening displays and, if necessary, engage in combat rather than retreating. This behavior reflects their instinctual role as protectors, particularly of treasures or sacred sites that cannot be easily relocated to safety.

In mythological Sanskrit texts like the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and Puranas, there is a race of powerful semi-divine snake beings called Nāga, capable of transforming between various formsm including human and full serpent forms. They dwell in underground areas near bodies of water. Despite their venomous nature, they often play benevolent roles in Hindu mythology, such as Vasuki aiding in the stirring of the Ocean of Milk. Their nemesis is Garuḍa, a bird-like deity.

In India, there is another legend about snakes. Generally known as “Ichchhadhari” snakes in Hindi, these snakes can take the form of any creature but prefer to transform into human form. These mystical snakes guard a precious gem called the “Mani,” more valuable than diamonds. There are many folk tales in India about greedy people attempting to seize this precious gem, all of which end in their demise.

7. Fertility

In Kerala, India, snake shrines are prevalent in most households, rooted in the belief that snakes were summoned by the region’s creator, Parasurama, to render the saline land fertile. Among these shrines, the Mannarasala Shri Nagaraja Temple stands out as a prominent place of worship. Its central deity is Nagaraja, a five-headed snake god believed to have been born to human parents as a blessing for their compassionate treatment of snakes during a fire.

Legend holds that Nagaraja, after fulfilling his earthly duties, entered a state of Samadhi but continues to dwell within a chamber of the temple.

In Asian countries such as China, Taiwan, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Cambodia, consuming snake wine—specifically made with venomous snakes like the king cobra—is believed to enhance sexual potency.

The process involves taking the snake’s venom while it is still alive and mixing it with various types of strong liquor or rice wine to enhance the flavor. In some Asian countries, the practice of soaking snakes in alcohol is also accepted. In this case, either the entire snake or parts of various snake species are submerged in strong liquor or rice wine.

It is believed that snake wine has beneficial effects on the body (and it is often sold at a higher price). One example is the Habu snake (Trimeresurus flavoviridis), which is sometimes soaked in Awamori rice wine by the people of Okinawa and referred to as “Habu Sake”.

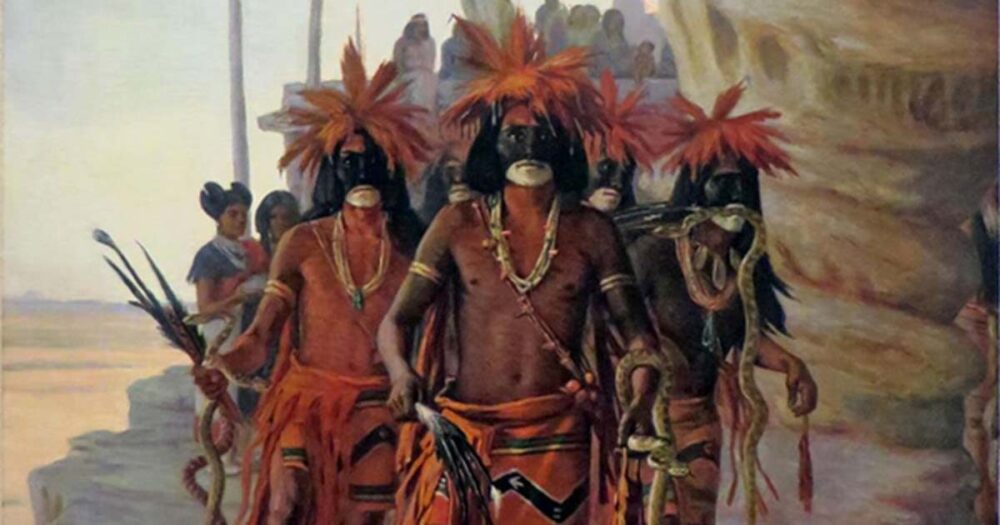

For the Hopi people of North America who perform a snake dance annually to commemorate the union of male and female snakes, snake symbolizes nature’s reproductive power. Many ancient Peruvian cultures worshipped nature. People in these cultures hold animals in high regard and often depict snakes in their artwork. Some indigenous tribes revere the rattlesnake as the king of snakes, believed to possess the ability to control wind energy or cause great storms. The Pueblo Native Americans associate the origin of songs with the underworld and the realm of snakes (when a snake is burned, its body fragments turn into songs).

In Southeast Asia, there are also stories similar to the White Snake tale, such as the one of Chu Dat Quan during the Yuan Dynasty in the literary work “Travels of a Monk of Fow”. It is recorded that the king of Champa had a “celestial palace” where he would ascend every night to a golden tower, where he would have sex with a woman transformed from a snake spirit, which serves as a prototype of the story of human and snake intercourse. Meanwhile, Khmer kings believed they had intercourse with a beautiful Nagini to maintain the royal lineage.

The snake symbolism of sexuality and fertility appears in one of China’s four great folk tales. Legend of the White Snake tells the story of Bai Suzhen, a powerful white snake spirit, who falls in love with a human named Xu Xian. Despite warnings from a Buddhist monk named Fa Hai about Bai Suzhen’s true identity, Xu Xian still marries her. However, Fa Hai intervenes, imprisoning Xu Xian and Bai Suzhen, leading to a climactic battle. After years of struggle, Bai Suzhen is finally reunited with Xu Xian and their son. The story highlights themes of love, sacrifice, good versus evil, and redemption. The story has been widely adopted into many mediums in Chinese arts.

8. Sin and Evil

The snake that tempted Eve is explained to be the demon Satan, or that Satan used the snake as a puppet, although this interpretation is not mentioned in the Torah and is absent in Judaism. Another Gnostic tradition suggests that Adam and Eve were created to help defeat Satan. Instead of being regarded as Satan, the snake is considered a hero by the Ophite sect.

In Japanese mythology, there is also a legendary eight-headed and eight-tailed snake dragon/serpent called Yamata no Orochi. Each head of Orochi corresponds to a human sin (ingratitude, disbelief, ignorance, foolishness, apathy, malice, shallowness, desire).

Izanagi (Japanese: イザナギ) is a male deity who created ancient Japan by stirring the primeval ocean with the divine spear Ame-no-nubuki, forming eight islands that became ancient Japan. One day, the goddess Izanami (wife of Izanagi) gave birth to Hinokagu, the fire deity. The flames engulfed her, leading to her death. Enraged, Izanagi cut Hinokagu into eight pieces. Each part of Hinokagu became different volcanoes.

After being severed by Izanagi, the spiritual essence of Hinokagu gave birth to humanity, becoming the Fire Deity. The evil essence, born from guilt towards the mother and resentment towards the father, accumulated within the eight volcanoes and every hundred years brought calamity upon humanity. The eight volcanoes, with their large sulfur deposits, formed the heads of snakes, converging to create Orochi.

Source: Apep sea serpent

The legend in Egypt also tells about Apep (known in Greek as Apophis) as a giant evil sea serpent, ruler of darkness and chaos in Egypt. The light of the truth of the goddess Ma’at makes the demon afraid. Apep was removed from ancient Egyptian worship because it was believed that such an evil monster could not be worshipped.

Once, the god Ra was traveling on the Barque boat when suddenly a huge wave rose, a giant sea serpent blocking the boat’s path. Ra ordered the monster to move aside, but it did not obey. Ra then hurled a spear at the monster. It recoiled and attacked Ra’s boat. According to the Egyptians, the moment Ra fought Apep is from dusk until dawn. When Ra encountered this monster was when the sun set. And when the monster retreated was when the sun rose.

9. Creation

In ancient civilizations, the snake embodied the spirit of the earth. It was god and at the fount of all cosmogonies. According to the beliefs of the Egyptians, Atoum, the snake, after leaving the primordial waters, gave the day to the gods, who, in their turn, created Geb and Nout, the air and the earth. Atoum was “the one who remains,” i.e., the one who was “on this side” and the one who will be “beyond.”

In ancient Indian mythology, the serpent Ahi or Vritra, associated with drought, swallowed the primordial ocean, only releasing all created beings when Indra split its stomach with a thunderbolt. Another myth features the protector Vishnu sleeping on the coils of the world-serpent Shesha, also known as “Ananta the endless.” Shesha, in turn, was supported by Kurma, and whenever Kurma moved, Shesha stirred and yawned, causing earthquakes with the gaping of its jaws.

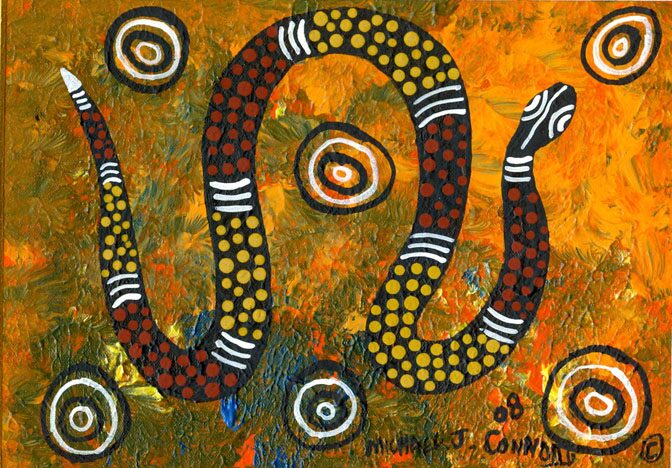

In Australian Aboriginal creation myths, the Rainbow Serpent is depicted as a deity responsible for shaping the landscape by creating mountains and valleys as it traversed the early, featureless terrain. Wherever it plunged into the earth, waterholes emerged and were replenished. The appearance of rainbows was believed to signal the return of the Rainbow Serpent, refilling waterholes and revitalizing the land.

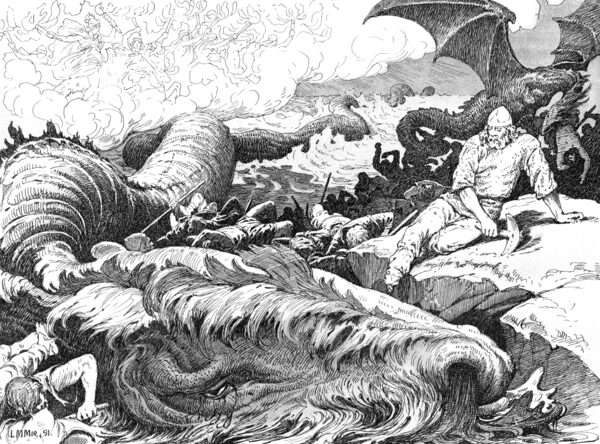

Another creation myth involving the snake is the Jörmungandr, or the World Serpent. Born to the god Loki and the giantess Angrboða, Jörmungandr is a colossal sea serpent that encircles the world, gripping its tail in its mouth. As it circumvents the Earth, it earns the title “World Serpent” or “Midgard Serpent.”

According to Norse mythology, Odin, the Allfather, threw Jörmungandr into the ocean that surrounds Midgard, the realm of humans. As the serpent grew, it became so large that it encircled the entire world, grasping its own tail. It is said that when Jörmungandr releases its tail, Ragnarök, the end of the world in Norse mythology, will begin. During Ragnarök, Jörmungandr is prophesied to battle against Thor, the god of thunder, in a cataclysmic confrontation that will result in both of their deaths.

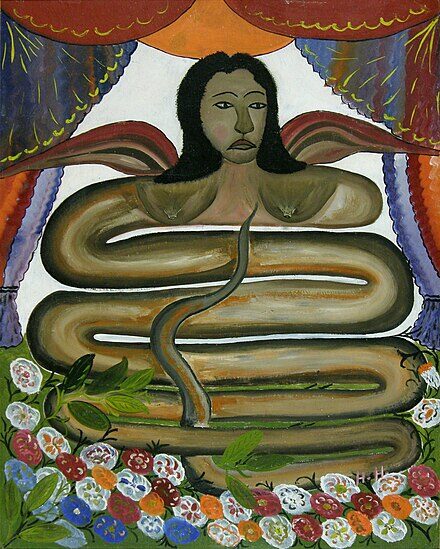

In the Haitian tradition, there is Damballa, often depicted as a black or white serpent. He is seen as the Sky Father in Vodou, is believed to be the first creator of all life. It is believed that he fashioned the cosmos by utilizing his 7,000 coils to shape the stars and planets in the celestial realms. By shedding his serpent skin, Damballa filled the Earth with water.

This serpent symbolism in creation myths are probably due to the fact that snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica. They are universal in human experience. This diversity has captivated human attention since ancient times, naturally leading to their inclusion in creation stories across cultures.

10. Eternity

The most well known snake symbolism for eternity is the ouroboros. The ouroboros is a powerful and ancient symbol depicted as a serpent or dragon eating its own tail, forming a circular shape. This symbol has appeared in various cultures and contexts throughout history.

At its core, the ouroboros symbolizes the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth. By forming a continuous loop with no apparent beginning or end, it represents the concept of eternal return, where each end is connected to the beginning, symbolizing the cyclical nature of existence.

In alchemical symbolism, the ouroboros is also associated with the concept of transformation and the alchemical process of dissolution and rebirth. It represents the cyclical journey of spiritual and personal transformation, wherein the individual undergoes a process of purification and enlightenment, leading to spiritual renewal and growth.

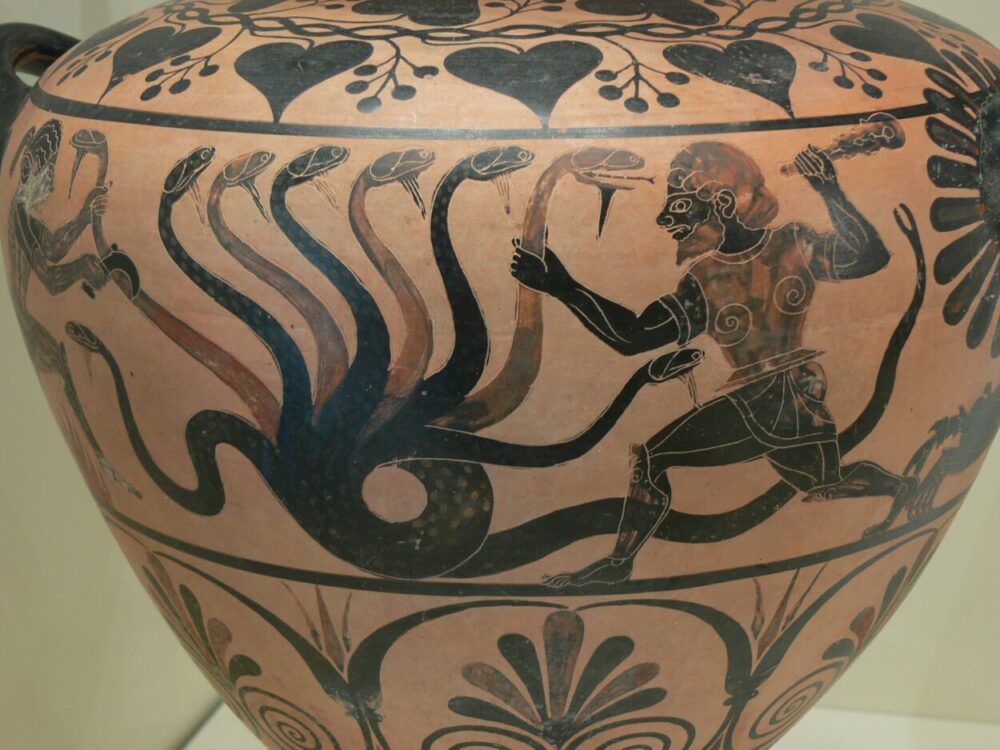

In the Twelve Labors of Heracles, one of the tasks was for Heracles to find and destroy the giant Hydra serpent with multiple heads. It had 17 heads. But whenever one head was knocked down or cut off, immediately two new heads would grow from the severed spot. This is the symbolism of endless regeneration (which probably stems from its skin-shedding capability).

11. Significance in Buddhism

Legend has it that six weeks after Gautama Buddha commenced meditating beneath the Bodhi Tree, the skies turned dark for seven days, and an extraordinary rain poured down. Yet, amidst the tempest, the formidable King of Serpents, Mucalinda, emerged from the depths of the earth, sheltering the One who embodies ultimate protection with his hood. Once the fierce storm subsided, the serpent king transformed into his human guise, respectfully bowed before the Buddha, and departed joyfully to his palace.

using WordPress and

using WordPress and

Comments are closed